Mechanics of Learned Reasoning 1 - TempoBench

Full title:Mechanics of Learned Reasoning 1 - TempoBench, A Benchmark for Interpretable Deconstruction of Reasoning System Performance

Introduction

Section titled “Introduction”As a small teaser and good high level overview, please enjoy our paper abstract:

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly excelling and outpacing human performance on many tasks. However, to improve LLM reasoning, researchers either rely on ad-hoc generated datasets or formal mathematical proof systems such as the Lean proof assistant. Whilst ad-hoc generated methods can capture the decision chains of real-world reasoning processes, they may encode some inadvertent bias in the space of reasoning they cover; they also cannot be formally verified. On the other hand, systems like Lean can guarantee verifiability, but are not well-suited to capture the nature of agentic decision chain-based tasks. This creates a gap both in performance for functions such as business agents or code assistants, and in the usefulness of LLM reasoning benchmarks, whereby these fall short in reasoning structure or real-world alignment. We introduce TempoBench, the first formally grounded and verifiable diagnostic benchmark that parametrizes difficulty to systematically analyze how LLMs perform reasoning. TempoBench uses two evaluation benchmarks to break down reasoning ability. First, temporal trace evaluation (TTE) tests the ability of an LLM to understand and simulate the execution of a given multi-step reasoning system. Subsequently, temporal causal evaluation (TCE) tests an LLM’s ability to perform multi-step causal reasoning and to distill cause-and-effect relations from complex systems. We find that models score 65.6% on TCE-normal, and 7.5% on TCE-hard. This shows that state-of-the-art (sota) LLMs clearly understand the TCE task but perform poorly as system complexity increases. Our code is available at our GitHub repository, you can find the paper on Arxiv.

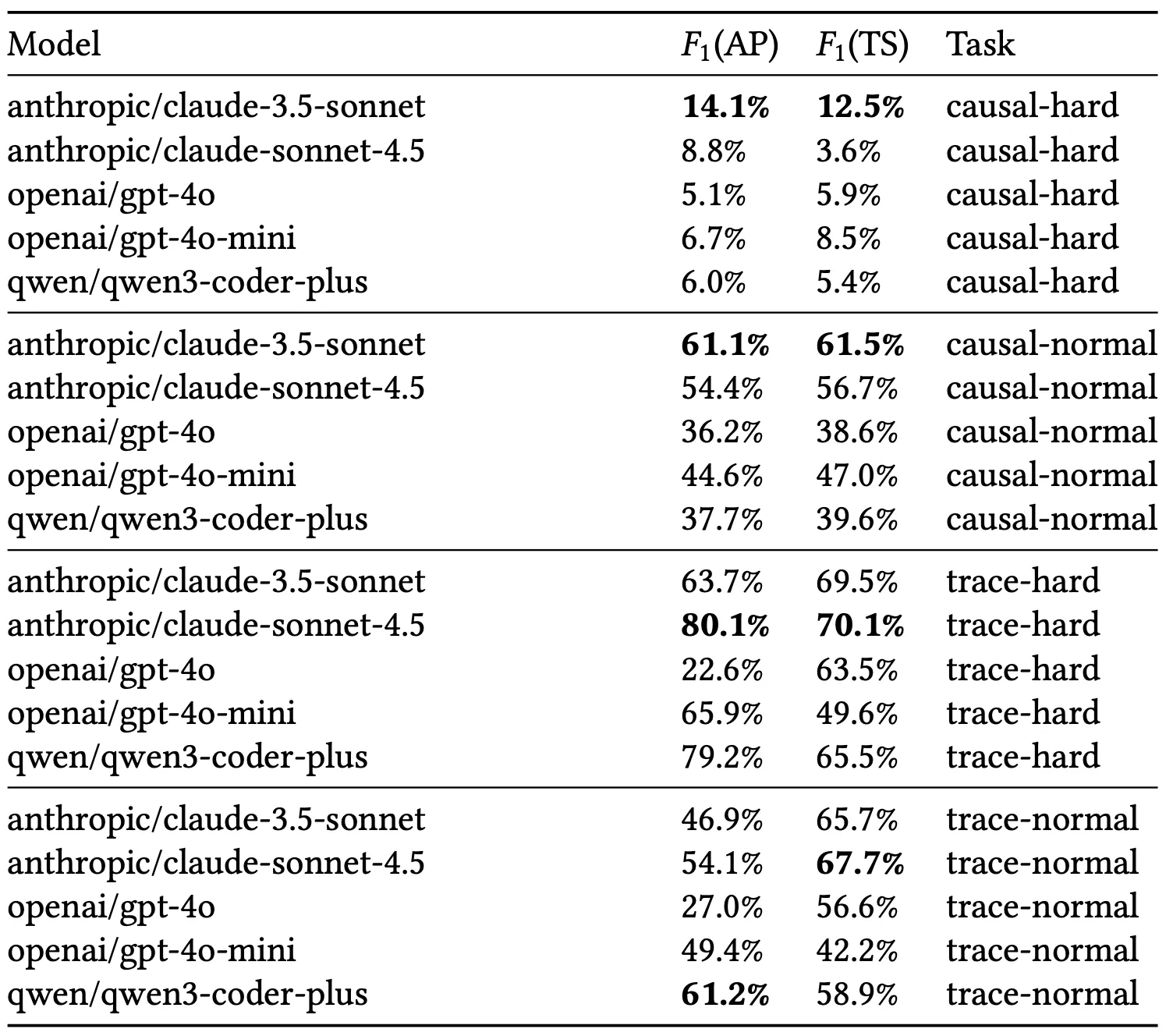

Here is a teaser of our results. We observe that various sota LLMs get consistently low scores across the tasks that are included in TempoBench.

Why should you care?

Section titled “Why should you care?”It is commonly accepted that LLMs by themselves are not that strong at reasoning, but require additional tricks or tools to perform these tasks. Previous works like Chain of Thought (CoT) or DeepSeek R1 to name a few rely on feedback loops where LLMs feed their “reasoning” output back into themselves to construct longer chains of reasoning. This behaviour has shown led to very strong results, outpacing humans on many “reasoning” benchmarks. This sparks two issues. First how do we design a good reasoning benchmark? Second why do LLMs perform how they perform on reasoning benchmarks?

In the first part of this series, we try to tackle these two questions and deconstruct how reasoning works. We also propose a new benchmark for LLM reasoning that is provably true, structurally parameterizable and infinitely scalable. This is a big advancement in the field of explainable reasoning, since to the extent of our knowledge, this paper is the first work to provide all of these guarantees. After the prelim section, I will elaborate on this point more. If you are familiar with LLM reasoning, temporal reasoning and formal verification, and state machines then skip that section.

Preliminaries

Section titled “Preliminaries”As mentioned, feel free to skip this section if you are familiar with these topics.

LLM reasoning

Section titled “LLM reasoning”Recent advances in LLM-powered reasoning agents have driven research on benchmarking and LLM reasoning capabilities. Methods such as Chain of Thought (CoT), self-consistency, and tree or graph-structured reasoning improve accuracy on reasoning benchmarks by leveraging intermediate steps or tool use. Other reasoning approaches leverage reinforcement learning (RL) to teach LLMs reasoning semantics and procedures, such as rl with human feedback, or reasoning traces collected over synthetic algorithmic coding problems such as CYCLE or SEMCODER. While such benchmarks are useful for holistic model evaluations, they are less amenable to dissecting the structure of reasoning or the factors that determine task difficulty. Evaluations often rely on aggregate accuracy or qualitative trace inspection rather than systematic analysis of reasoning complexity. In contrast, TempoBench grounds reasoning evaluation in formal, parameterized systems, enabling quantitative study of how reasoning performance scales with structural problem features.

Temporal Reasoning

Section titled “Temporal Reasoning”

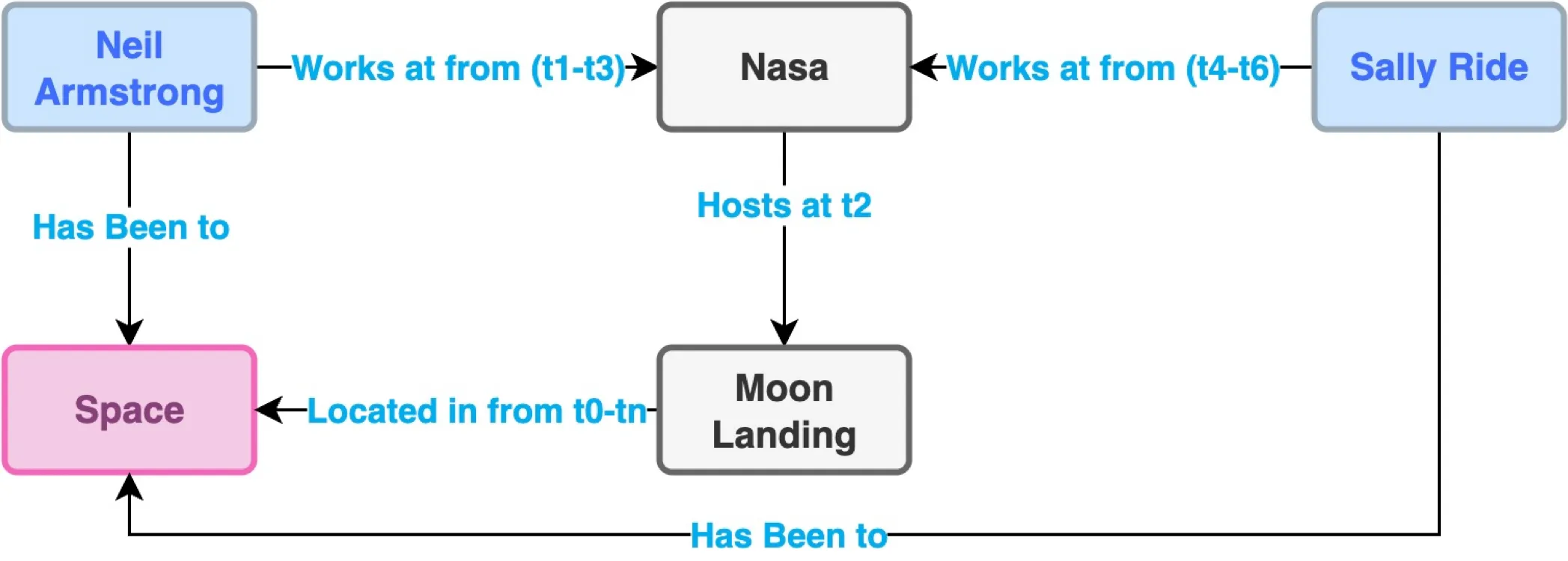

Figure: Sample knowledge graph showcasing relationship inference and how knowledge graphs can be “hacked”. In this trivial example case, asked to determine who has been to the moon, the LLM is highly likely to have prior knowledge of this fact. This k-graph problem generalizes beyond this trivial example, and it is extremely important for benchmarks not to expose vulnerable k-graphs that LLMs could exploit to “reason” better.

Temporal reasoning benchmarks are difficult to curate because of the complexity of extracting temporal transitions from real-world systems and of verifying ground-truth causal relationships. Sota benchmarks are generated through three primary methods: LLM-generated synthetic temporal knowledge graphs, assigning temporal structures to randomly generated graphs, and human-curated data sets. Temporal knowledge graphs, as shown in the figure above, are a widely used approach for representing relationships among entities over time. They are easy to construct and check, forming the basis for benchmarks such as TGQA. These graphs are generated from real-world or synthetic LLM data. Despite their popularity, they present four limitations for evaluating temporal reasoning:

- Graphs built from real-world data often enable models to rely on prior knowledge, making it difficult to isolate an LLM’s temporal reasoning ability.

- Relationships are overly simplistic, an edge between two nodes denotes a relation, but real systems often involve multiple interacting inputs and outputs that are not all causally linked.

- Task difficulty is hard to quantify, as it depends simultaneously on linguistic, symbolic, and temporal complexity.

- Synthetic data generated by LLMs lacks verifiability and typically requires human validation.

TempoBench addresses these challenges by generating temporal traces from automata synthesized from formal specifications describing real-world systems—such as arbiters and controllers. Temporal logic yields temporally rich, verifiable data. Furthermore, causal relationships are explicitly synthesized for outputs, ensuring that causal inputs are formally validated. TempoBench uses the HOA file structure, a structured, interpretable formalism, to reduce reliance on pure symbolic reasoning. Ultimately, these formalisms provide more insight into the difficulty of the variant temporal-reasoning tasks our benchmark addresses.

State Machines

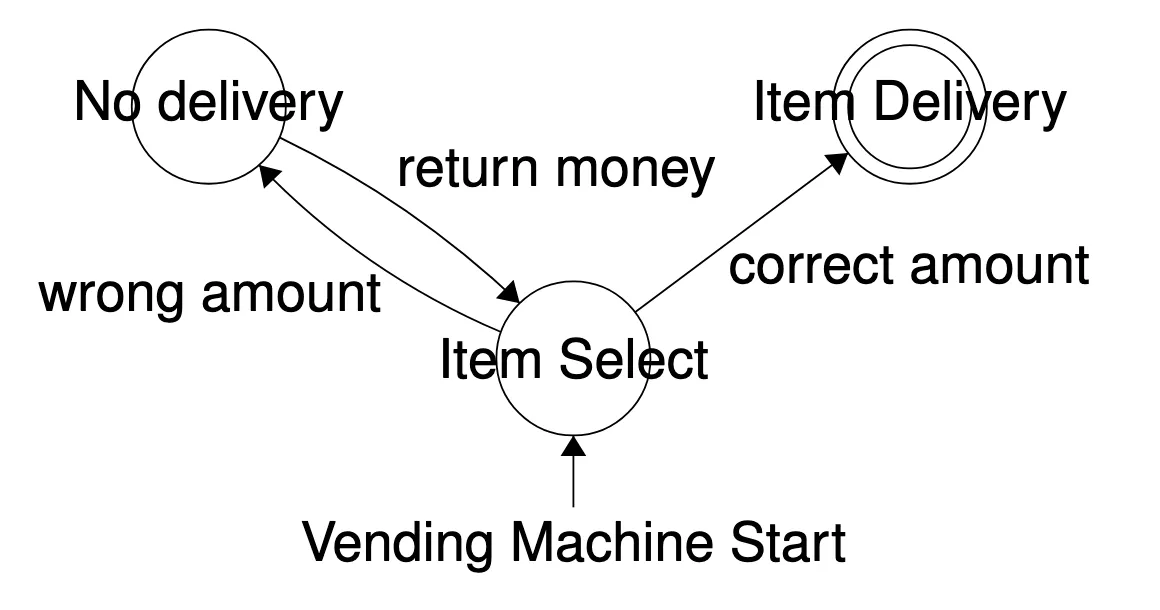

Section titled “State Machines”Very briefly I want to introduce you to the concept of a state machine in computer science. State machines break a problem into states and transitions.

Figure: suppose this example state machine that models a vending machine. You can see how this system models the possible interactions that someone can have with the vending machine, where an action will take you to a state. So when we begin interacting with the machine, we are at the state item select if we enter the correct amount of money then it goes to item delivery the two circles at this state, tell us that it is an accepting state, which you can interpret as a successful interaction. If we enter the wrong amount, we go to no delivery. From there, the money is returned, and we are back at item select.

You can see how this mirrors some reasoning process. Being able to interact with a vending machine, requires some understanding of what state you are in, what state you want to go to and how to get there. Nailing exploration of this behaviour in LLMs is hard, and it is what we aim to do in TempoBench.

Tasks and Significance

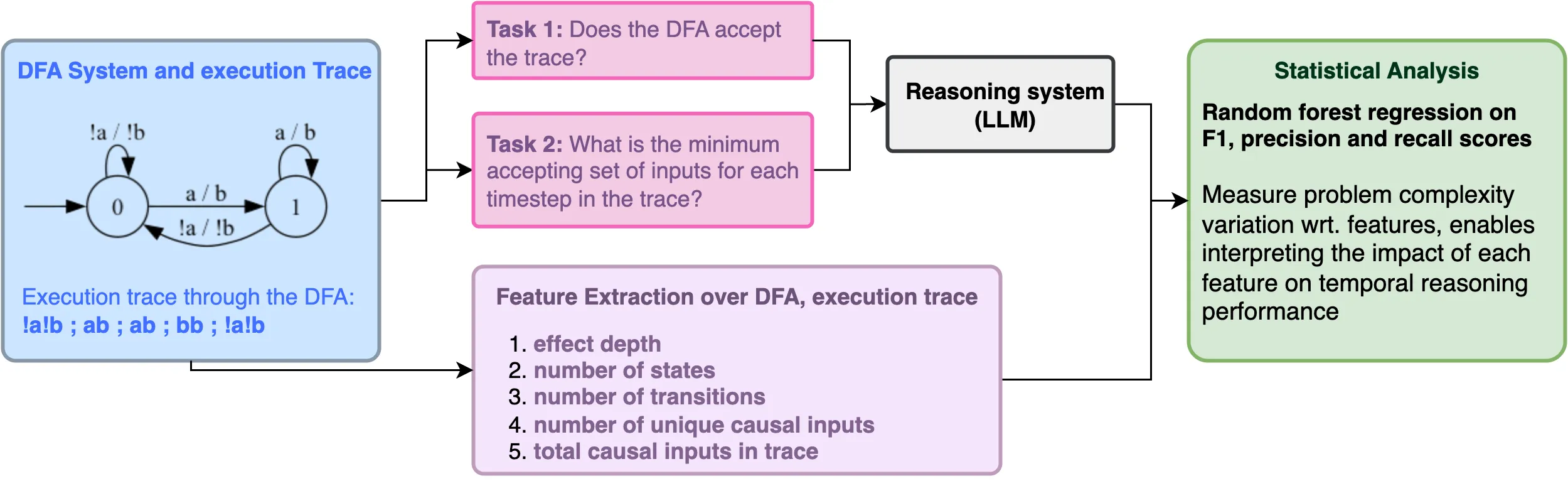

Section titled “Tasks and Significance”TempoBench consists of two tasks.

-

Temporal Trace Evaluation (TTE). Given a finite-state machine and a finite trace , determine whether is accepted by . To do so, walk through the transitions of the state machine, and at each time step , verify whether the set of inputs and outputs is accepted by . This task unifies elements of runtime verification and world modeling. The model must determine whether the observed behavior satisfies the temporal constraints imposed by the system; it must also reason over the system’s transition dynamics sufficiently to interpret the current state and navigate subsequent transitions within that structured world. The TTE task is a good measure of how well models perform retrieval from their inputs, as they must accurately parse and apply the HOA’s state transitions. See Appendix for the HOA file representation and its automaton counterpart. As such, we use the TTE task as a litmus test of how well the models understand the HOA file format for state machines and natural language representations of their traces. Bad performance on this task suggests that the models are confused at the language level and that problem difficulty is biased by complex representations rather than by structural indicators.

-

Temporal Causality Evaluation (TCE). Given a finite-state machine , a finite trace generated from , and an effect that occurs at some time (where is the set of outputs ), generate the causes at each that were necessary for to occur at . At its core, this task tests the model’s ability to reason causally through time. (for more information on temporal causality and synthesis of temporal causality see Appendix).

Long form results

Section titled “Long form results”If you’ve made it this far, congrats and thank you for reading. I hope you’ve been enjoying the experience so far. No research project is complete without some cool results and graphs. Below are the findings of this paper, a hopefully convincing and interesting deep dive into reasoning in LLMs.

The results are broken down into two sections. First, we compare the reasoning performance of various state-of-the-art LLMs on TempoBench. Then we perform statistical analysis on the model scores within TempoBench’s feature space.

Model Results

Section titled “Model Results”

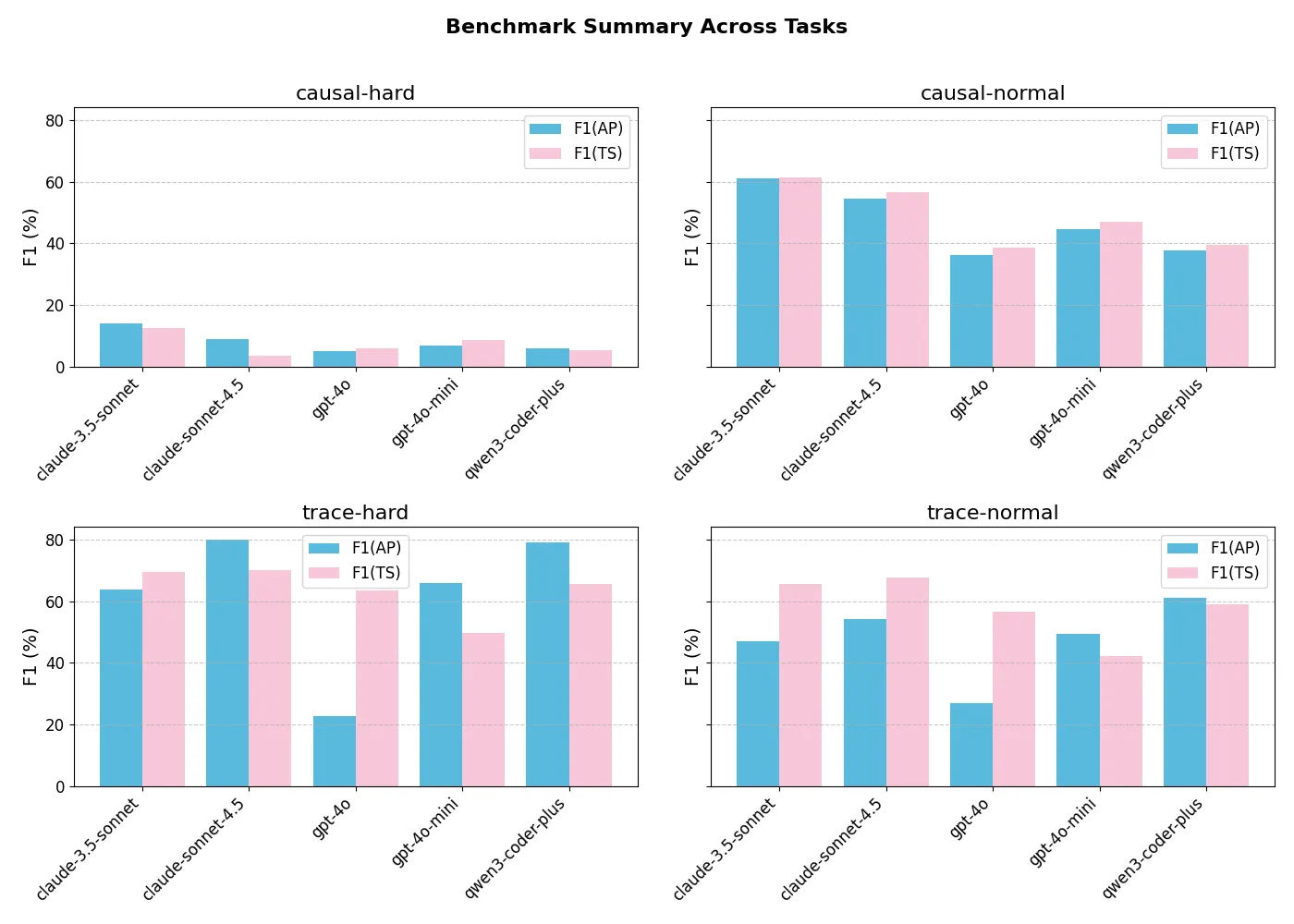

Figure: Visualization of results across all benchmark tasks. TTE normal and hard, TCE normal and hard.

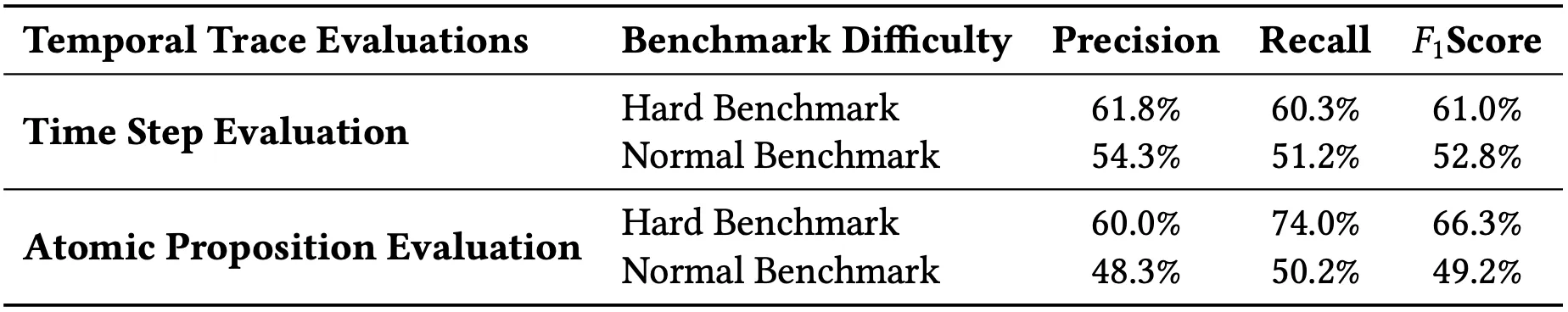

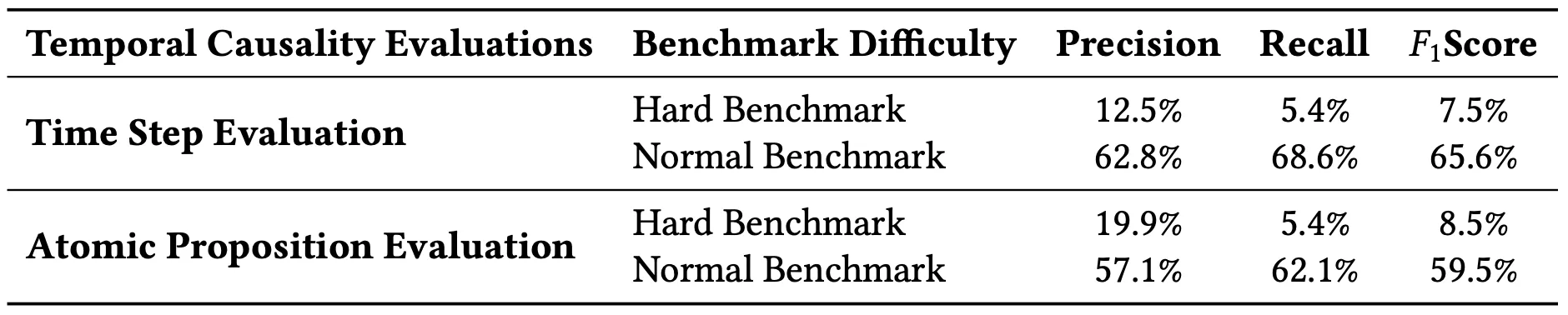

Figure: Averaged results across all benchmark tasks. TTE normal and hard, TCE normal and hard. Averaging across tasks lets us examine the problem difficulty in a model agnostic way. We care just as much about what makes a problem hard than about how some sample of LLMs perform on these problems. Our results demonstrate that we can effectively split datasets blindly into normal and hard very well, which validates our measures of difficulty.

The F1 scores are measured across the two benchmark tasks, split into hard and normal, at the Atomic Proposition (AP) and Timestep (TS) levels. The F1 scores are evaluated against the ground truth, as seen in the listing. F1(AP) measures the performance of the model at predicting the correct APs within each timestep, allowing partial correctness within a single timestep. F1(TS) assesses model performance by predicting the whole at each timestep. It is important to note that tracking performance at the AP and TS level lets us see how much the models are guessing. If a model does well on AP, but poorly on TS then it means it’s just guessing randomly within each TS. It is also important to note that randomly guessing does give negative scores so some models (GPT-4o) that have worse TS than AP performance are indeed randomly guessing.

Example Illustrating F1(AP) and F1(TS). Let the ground-truth trace and model prediction be:

F1(AP) compares individual atomic propositions within each timestep. For instance, overlaps occur at : , : , : , yielding partial matches. Thus, F1(AP) rewards local overlap: , , . F1(TS) considers each timestep correct only if all APs match exactly. Since none align (, etc.), . This captures full temporal correctness rather than partial AP overlap.

Roughly, F1(AP) asks how well models get mostly correct answers at most time steps, while F1(TS) asks how well models get all the correct answers for an entire timestep. There is no strong relationship between their performance on TTE and TCP tasks, suggesting these are truly distinct temporal reasoning tasks. The table shows our results across various LLMs.

Our analysis of absolute model performance demonstrates that TempoBench presents a challenging yet tractable benchmark. All evaluated models successfully solve a nontrivial portion of the problems—partially or entirely—showing that the tasks are well-calibrated in difficulty. Notably, TCE-hard proves substantially more difficult than TCE-normal or either TTE variant, validating the effectiveness of our difficulty features. This trend is consistent across both F1(AP) and F1(TS) metrics. Interestingly, models exhibit higher scores on temporal-hard AP but lower scores on temporal-hard Timestep tasks. This discrepancy arises because hard samples contain more inputs—allowing models to achieve higher overlap scores within individual timesteps without genuinely resolving the underlying temporal dependencies.

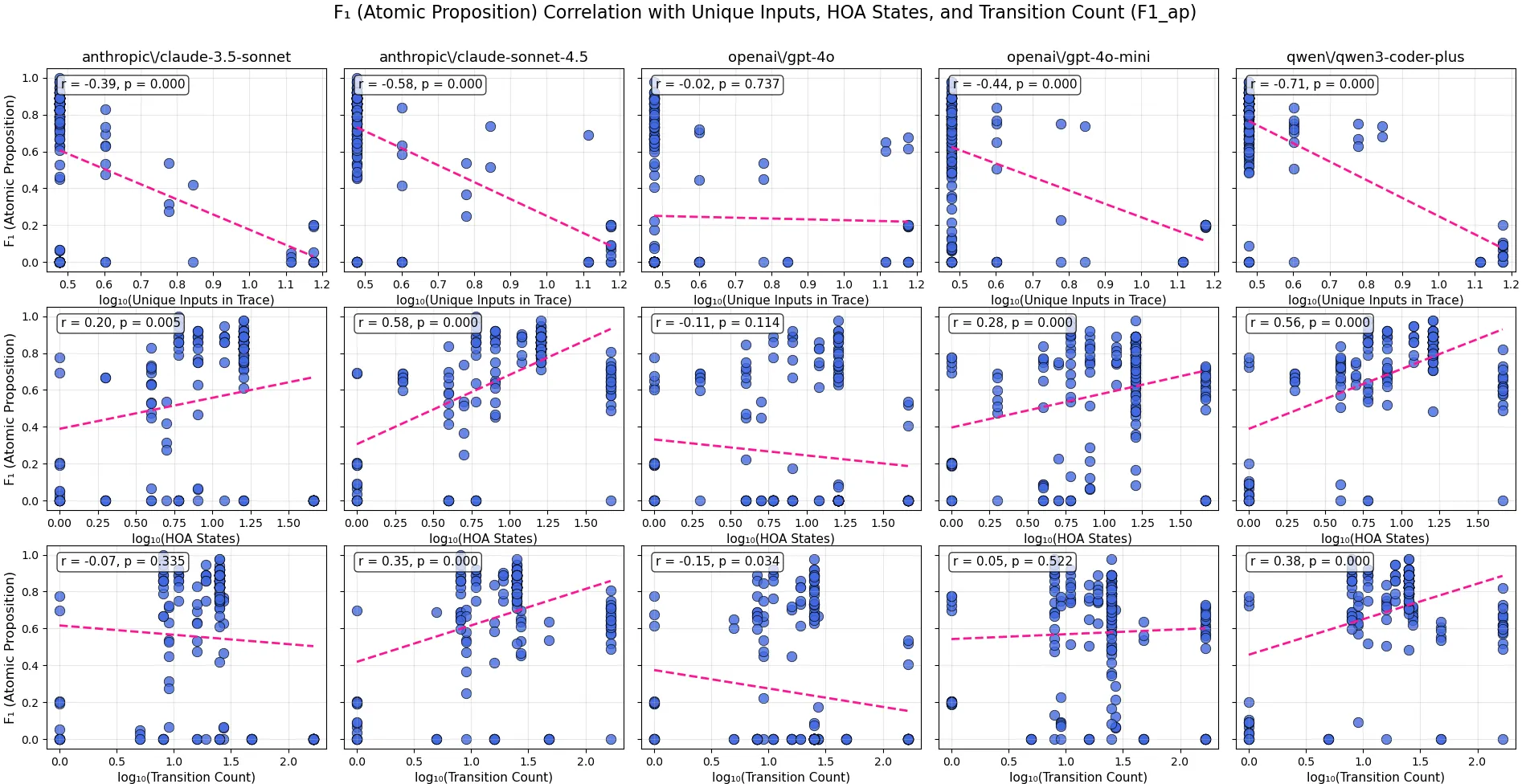

The figures show correlations between F1(AP) scores and transition count and system states for the TCE task. Each scatter plot includes a line of best fit and correlation statistics, showing that the negative relationships between these parameters and the F1(AP) scores are statistically significant. The p-value of indicates that observing such a negative relationship by chance is extremely unlikely. These graphs provide a useful in-depth understanding of the specific LLM reasoning capabilities. For example, it is surprising that Claude-Sonnet-3.5 outperforms the newer Claude-Sonnet-4.5 on TCE tasks. As shown in the figure, F1(AP) scores for Claude-Sonnet-4.5 exhibit stronger negative correlations with transition count and HOA state ( and ) compared to for Claude-Sonnet-3.5, suggesting that the earlier model generalizes more robustly and is less sensitive to increases in system complexity. We hypothesize that recent LLMs are increasingly optimized for the multi-context protocol (MCP), prioritizing flexible tool and agent coordination over deep internal state modeling, which may explain their weaker performance on tasks that require reasoning over large latent state spaces.

Figure: Correlation scores for (unique_inputs_in_trace), (hoa_states), and (transition_count) versus F1 scores at the Atomic Proposition step, with corresponding p-values denoting statistical significance. This figure covers the TTE task.

The TTE task reveals a different sensitivity pattern across features as seen in the figure. There is a negative correlation between the number of unique inputs in the trace and the F1(AP) score for all models except for GPT-4o. There is a positive correlation between F1(AP) and the number of system states for all models except GPT-4o and Claude-Sonnet-4.5, which exhibit neutral and weak positive correlation, respectively. Surprisingly, GPT-4o performs much worse than other similar models across all of these tasks, including GPT-4o-mini, which not only outperforms GPT-4o but is also on par with newer models like Claude-Sonnet-4.5. The positive relationship between system states and F1(AP) score illustrates that the model only needs to know its current state. The figure shows that modern LLMs have become very strong at symbol mapping and retrieval, yet still struggle to perform more complex temporal reasoning. The results in the figure show a negative correlation with the number of inputs; the number of constraints on transitions between states mainly determines TTE difficulty. Importantly, the high performance on TTE across both hard and normal conditions indicates that all of these models can understand the HOA format. This demonstrates that while there is variation across models, the HOA file format is not a limiting factor in performing this task.

Statistical Analysis

Section titled “Statistical Analysis”

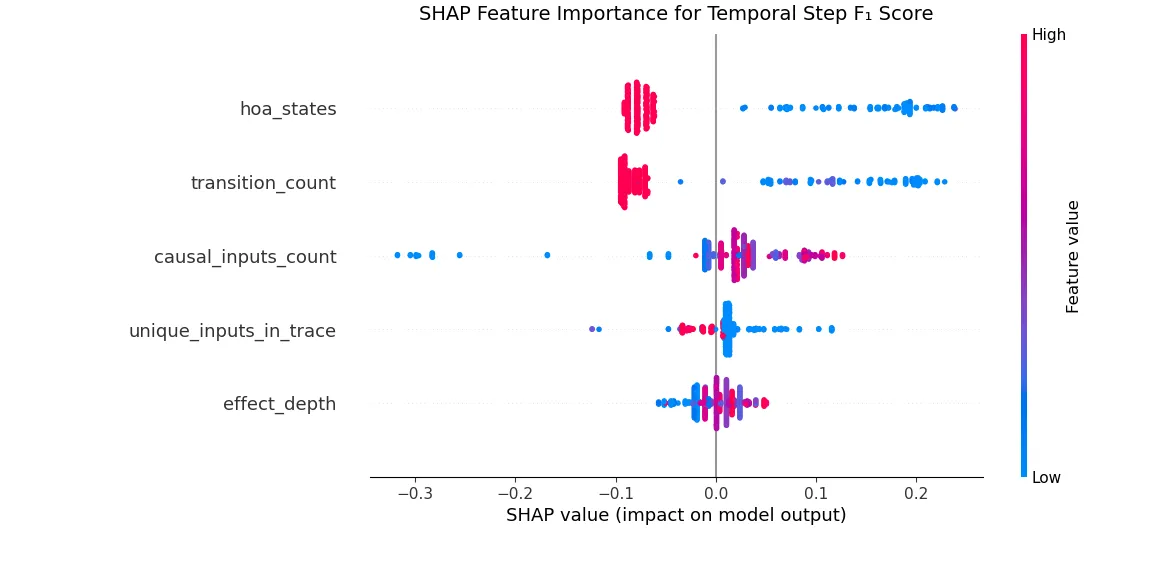

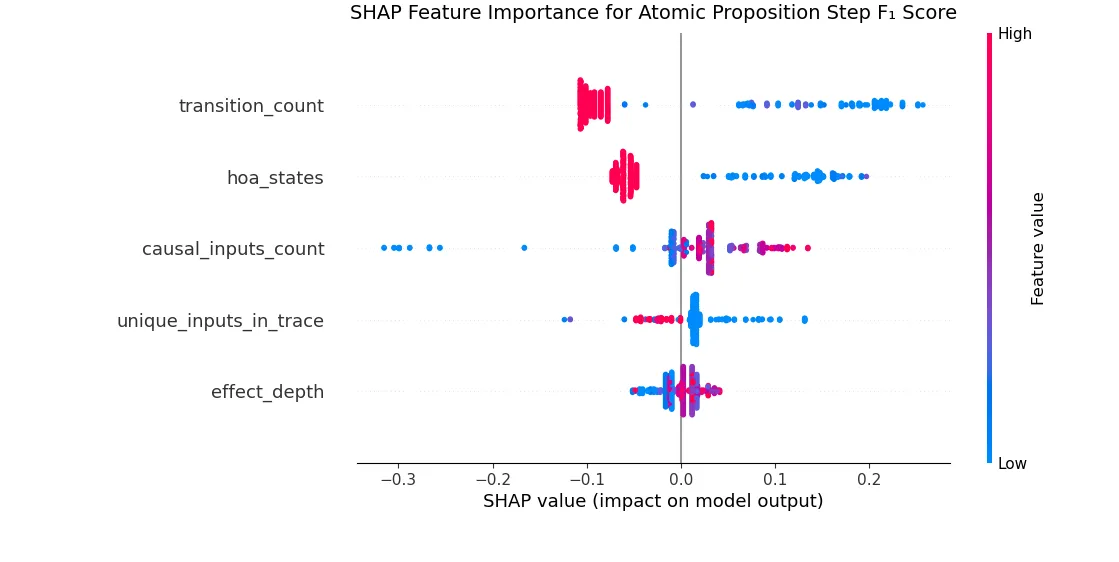

**Figure:**SHAP Beeswarm plot representing feature importance and correlation with Temporal Causality Scores at Atomic Proposition Step

We report precision, recall, and F1 scores using two evaluation schemes on the Timestep and AP levels. Although results aggregate all models, per-model parameter–F1 trends remain consistent (see Appendix for per-model SHAP plots and ). The results in the table highlight the increased difficulty of this task for more complex systems. We further illustrate this with SHAP plots derived from random forest models trained to predict F1(TS) and F1(AP), respectively. Random forest regression is used because the F1 distributions deviate from normality as shown in the Appendix making simpler models such as Ordinary Least Squares regression inappropriate. The SHAP plots highlight both the relative importance of each feature and the direction of its influence on the F1 Score. For instance, the number of system states emerges as a key feature: higher state counts generally negatively affect F1, and when the relationship is positive, the effect is comparatively weak. Lastly, the features are listed from most important to least important. The random forest models for predicting F1(AP) and F1(TS) achieve scores of 0.646 and 0.66. represents the amount of our F1 scores explained by the predictors. These scores indicate that in our temporal causality task, the majority of the variation in the F1 score is explained by the customizable parameters of the benchmark. The remainder is explained by variation in LLM performance on temporal causality.

Given the strong model fit indicated by the score, the SHAP values provide meaningful insights into how increasing automaton complexity hinders LLMs’ ability to perform temporal credit assignment. Features such as the number of states, transitions, and unique inputs emerge as key drivers of difficulty, aligning with intuition. In contrast, traces with more causal inputs show higher F1 scores because a greater number of distinct causes reduces

Conclusion

Section titled “Conclusion”In summary, we present TempoBench, a generative, synthetic, and formally verified benchmark for temporal reasoning. This diagnostic-focused benchmark is created using formal methods tools for reactive program synthesis and causality analysis. In this work, we introduce TempoBench as a formally grounded benchmark for evaluating temporal causality and credit assignment, and demonstrate its utility not only as a benchmark but as a full diagnostic pipeline. TempoBench benchmarks offer critical advantages for analyzing and interpreting LLMs, including verifiability, compositional structure, and scalability to large state spaces. Unlike prior temporal reasoning benchmarks that primarily serve as leaderboards, TempoBench is explicitly designed as a diagnostic tool — enabling researchers to probe failure modes, trace causal reasoning, and study alignment with formal system dynamics, rather than merely measuring task performance. Using TempoBench, find that reasoning over systems with larger problem spaces and more logical transitions does increase complexity. However, our results also demonstrate that, in many cases, larger systems with more transitions have a higher density of connections between states, making it easier for LLMs to track chains of reasoning through them. Our results show that temporal causality is complex for LLMs, with score on TCE tasks dropping by on average across TS and AP. By identifying the structures, such as system states and transition counts, we aim to help diagnose these system failures so that future LLMs can perform better on such temporal reasoning tasks.